As part of our new exhibition, conFRONTation, a storefront exhibition in Berlin Mitte, we showed Elham Angell's artwork “The lines and a tree”. In a conversation with the artist, we explored her change from doing science to doing art, her thoughts about Persian literatures connection to nature and more.

CAC: What is your climate change story? Could you share your journey in understanding climate change and when you started creating climate art?

Elham: I did art related to nature and the environment, basically the earth, but before I started doing art, I was working as a scientist, and I particularly worked in environmental matters. About climate change, the pandemic was my turning point. During the pandemic, I understood how vulnerable we are to nature. We always have this illusion as humans, that we are so powerful and have power over nature, but the pandemic showed that's not true. We are very vulnerable and small! During the pandemic, when we stopped our activities, our traffic, we saw that nature was starting to heal itself.

That was when I thought, "Okay, maybe we still have time."

I wanted to express myself and my thoughts about climate change and raise awareness. Because to be honest, we are turning our beautiful blue planet into an alien planet that we don't know anymore, and we are not evolved for that.

I can say I was always into environmental matters, but climate change specifically was because of the pandemic. I sought to think about it, and I did many artworks during that time related to climate change.

CAC: You did a master in geology before. What got you interested in creating art full time and quitting your job as a scientist?

Elham: I studied geology engineering, a field of geology that focuses on the effect of human activity on the Earth and the Earth's effect on our lives and I was working in environmental departments. I have always had these two characteristics, art and science, in me at the same time. I could never say if I'm an artist or a scientist, but professionally, I was working as a scientist.

My turning point was a project I did that was related to the environment. I was super happy about the results. I showed the results to the authorities and expected them to take action, but nothing happened. I realised that this was my limitation in science. You have this limitation. You cannot do more than this.

I thought, "I have reached the highest point I wanted to be in science and geology. Now it's time to start my art life, where I have a voice and can communicate more and talk more." So basically, I changed my angle, but I was always in between the two subjects: art and science.

CAC: Do you incorporate your scientific knowledge in your art?

Elham: Definitely. It's all about that, because when I'm working or thinking about something, I always incorporate my knowledge of science, specifically about the Earth. For example, in land art, you need to know about the Earth, because it's your gallery space, isn't it? From the idea of a project to creating and presenting it, I'm always thinking with my science background. I've planned to move to more art projects that involve science. My next project will have even more science involved. It's about plant life and its relation to humans.

CAC: Let's talk about the lines and the tree, the artwork, which we're going to show. Could you tell us a bit about the creative process behind it? How did you create it?

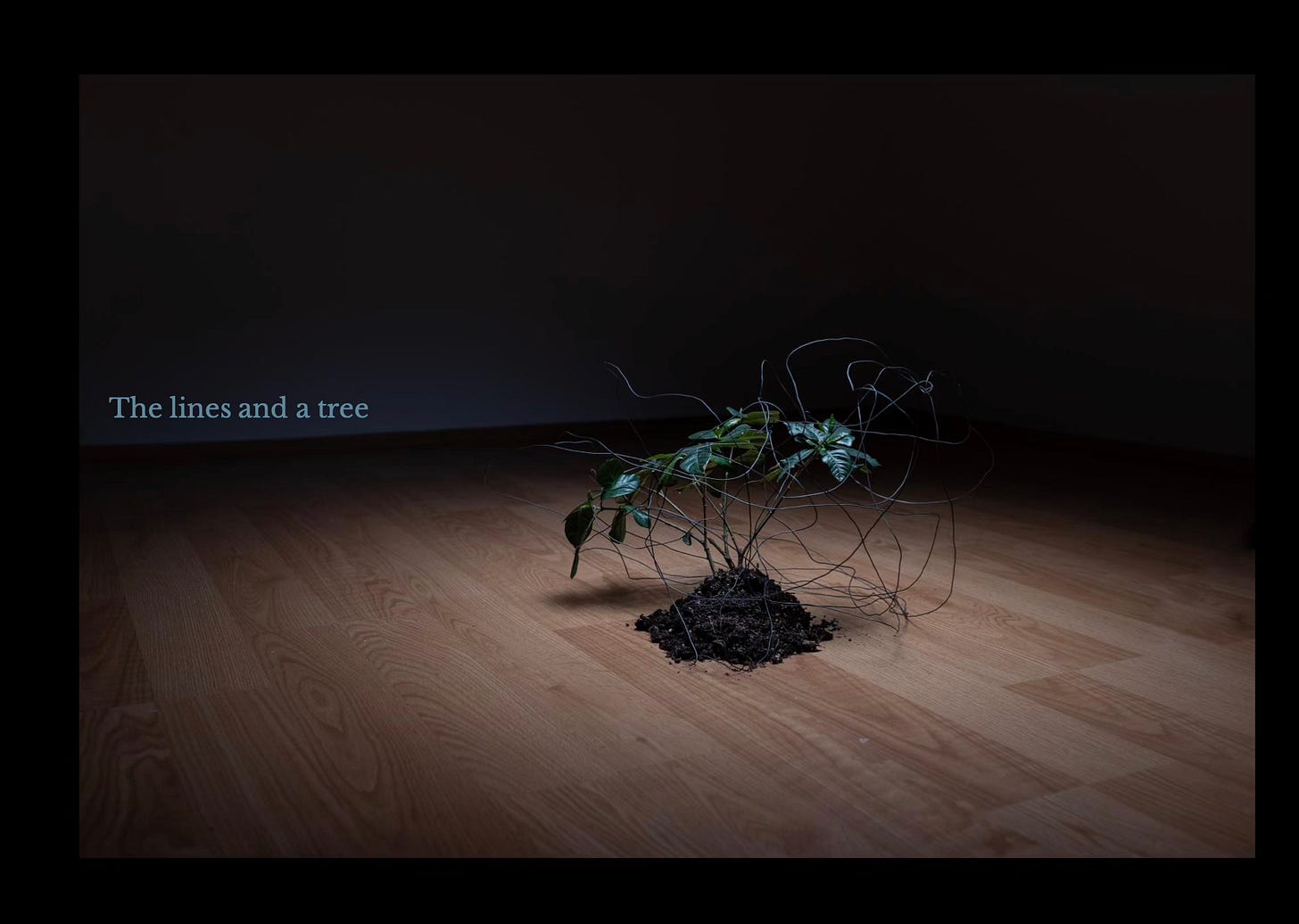

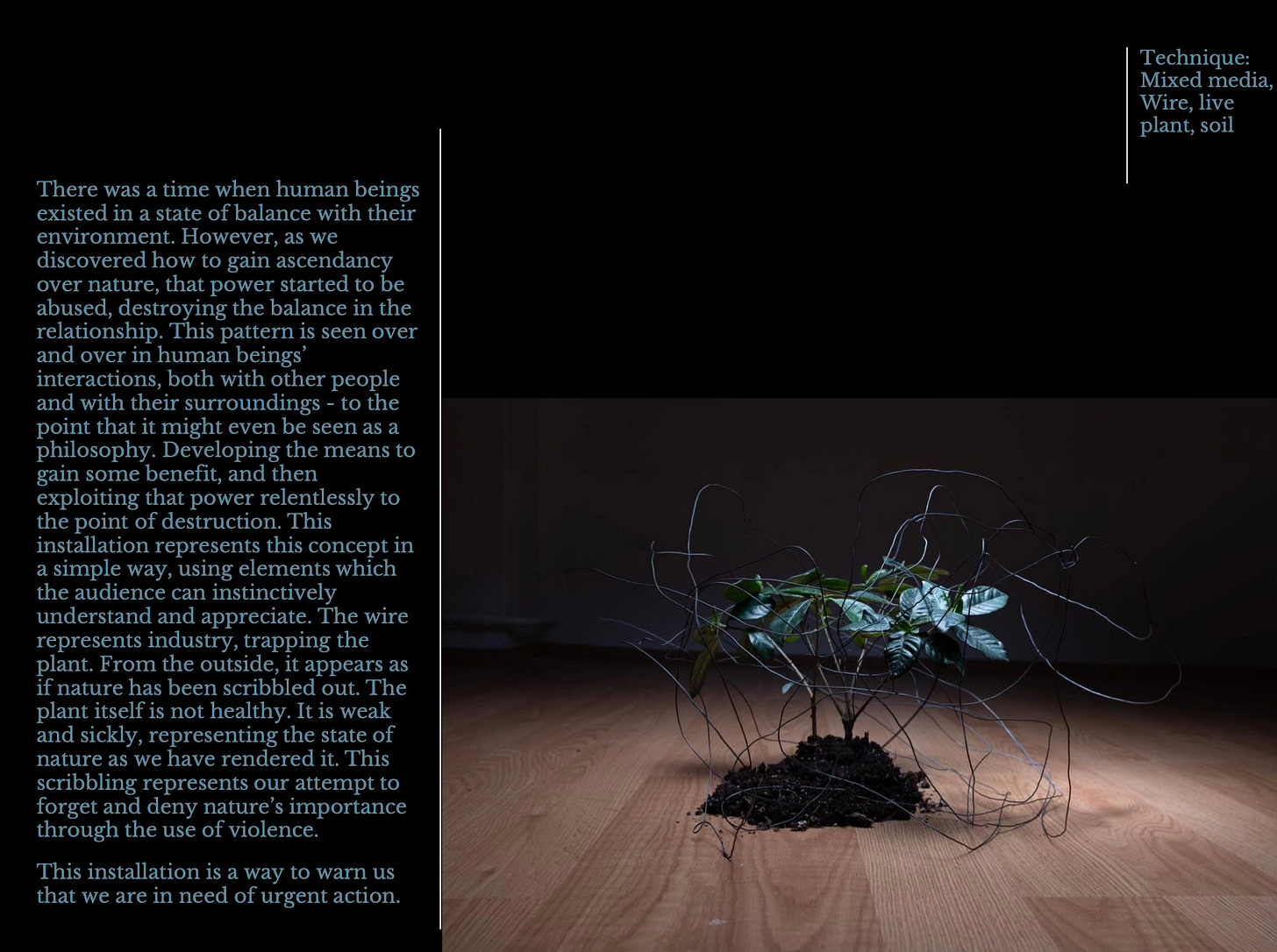

Elham: It is a funny story. I told you about how climate change occupied my mind during the pandemic. And at that time, I was once in a very big department store, and I saw a plant. It was very weak and vulnerable. And if I see a plant, I know if it will survive or not. I knew that it would be very hard for this plant to survive, because it was obviously in a very bad condition. Suddenly, an idea came to my mind: our environment is also very vulnerable and very close to dying, just like the plant. The whole concept and structure of my story came to my mind in the shop with that plant. That object inspired me.

I had this simple wire, but the effect of it is very close to the effect of a pencil, visually. Even if you touch it, your hands can get black. So, I took the plant in the studio and told my photographer how I wanted the light to shine just on the plant and the surroundings to be dark, to show its loneliness and vulnerability, just like it was in the shop. It was weird. It was a tiny event, but that came out of it.

CAC: You mentioned the philosophy that objects carry for you. How is Persian literature connected to your artistic process and maybe also connected to climate or the environment?

Elham: So, in both Persian classic and contemporary literature, you can see this care for the environment. In classical literature, many poets talk about elements of nature. Specifically, I love how they describe the face and beauty of their beloved subject, using different elements of nature in their texts.

Elements of nature are used as symbols. My favourite is the cypress tree, which you can find in Tuscany. In Iranian literature, cypresses represent freedom.

This is true in classical literature, but also in contemporary literature. One poet, Sohrab Sepehri, specifically talks about taking care of the environment, not harming other animals and creatures. He argues that the environment is intact and that we are part of the system. He does this in a poetic way, of course.

Sepehri was a painter and a poet. I will translate his words for you word for word, but of course, it is more beautiful in Persian. He says: "Let's not wish the fly to vanish from the fingerprints of nature." In another poem, he says: "There was an emptiness in the minds of the sea before corals."

Both in classic and contemporary literature, nature and respect for nature are always present. It feels like this helps us to look deeper, to see behind the objects. For example also, in Rumi's poems, you often see that objects carry meaning or philosophy.

Persian literature is a great inspiration for me.

CAC: Do you and if yes, how do you make climate change tangible and emotionally resonant - feelable for your audience?

Elham: I want to specifically talk about land art because I think it is a unique medium that uses the Earth itself as its canvas. It is especially useful for involving the audience emotionally, as the gallery space becomes nature itself, automatically creating an emotional connection between the audience and the environment.

I try to present my art in a simple but creative way. I want my art to be accessible to everyone, regardless of their background, especially when it is about climate change. I don't want to target a specific audience, but rather raise awareness among the general public. If my art is too complicated, it will be difficult for people to understand and connect with.

I also believe that it is important to be careful about how I evoke emotions in my audience when it comes to climate change. I want to avoid making them feel guilty or sympathetic. Sympathy is not a strong motivator, as people may feel that they have done enough simply by feeling bad for the victims of climate change. Instead, I want to evoke empathy in my audience, which will make them more likely to take action. When people feel empathy, they put themselves in the shoes of others and are more likely to want to help.

CAC: Have you noticed any lasting impact on people?

Elham: I don't expect my art to have an immediate effect on people the moment they see it.

I think of climate artists as a team. We may not know each other, but when we talk about the same things, such as climate change, step by step, letter by letter, we raise awareness.

Specifically, what I really like about confrontation is the location. It's not in a gallery space where people deliberately go to see something. It's in a public space.

I think artworks should generally be presented like this. Imagine someone coming back from work and seeing the artworks there. They have a few seconds to think about it. That's enough. Because tomorrow there will be something else, maybe a scientist will say something. In the end, it makes a huge difference.

But if I want to talk about my long-lasting impact, I should talk about my work. I practice contemporary art with children. Many of my projects are related to the environment and climate change. The children are very young. And I think that's my real impact on the future, because they are at an age where everything plays a fundamental role.

CAC: Do you see yourself in general as an activist?

Elham: I can't really call myself an activist yet, because I think I should be more active and do more.

I understand that this is partly due to my circumstances in recent years, my location, and other factors. But if I want to be honest, even before I entered the art world, most of my research in my scientific practice was about the environment and environmental issues. So, in a way, yes, but not enough.

CAC: So beyond individual, visual efforts, what do you think should like in like a political sense, what strategies should there be to not reach this point of no return on climate change?

Elham: That's a very interesting question. About two months ago, a new research study was published by a very famous scientist. I can't remember his name, but he said that based on his results, we still have time to undo climate change and global warming. However, we need to act on a large scale, like at the country level. So politicians need to be involved.

But that doesn't mean that people can't do anything. I believe that people can make politicians take action on climate change, especially in democratic countries, because they need people's votes. In many countries, if you are an environmental activist or a scientist, you can be imprisoned. In my country, a group of scientists and environmental activists are in prison. But in democratic countries, people can be heard.

I think it is the responsibility of artists and scientists to work together to raise awareness about climate change. I believe that the path to reaching politicians is through the people.

CAC: Thank you very much for your time!

more: